Click here to read this essay on Substack.

It's quite possible that the American media landscape has never been as chaotic or fragile as it is today. Infamous billionaire Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post. In June, The New York Times published an op-ed from a Republican senator suggesting the military should be sent in to violently quell protests in the streets. Outlets across the board including Refinery29, Vogue Magazine, and Bon Appetit have been outed for institutional racism, and even more outlets like VICE, The Atlantic, and Conde Nast laid off substantial staff, many of whom were women or people of color, citing budget restraints amid the pandemic. It seems the decline of traditional journalism has been a long time coming: interest in print media has been decreasing for decades, but today even established online publications don’t seem to be safe: several niche, mission-driven, nonprofit journalism projects like Study Hall and Unicorn Riot have gained popularity as of late, and many are turning to Twitter for live updates or first hand accounts about protests instead of relying on the news. Most recently, an even more surprising outlet has joined the party: Instagram.

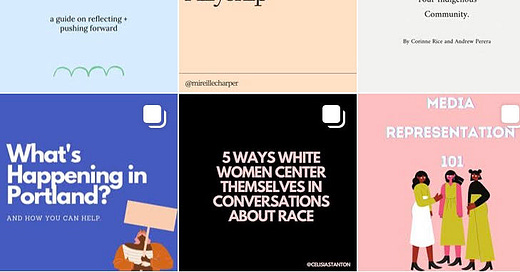

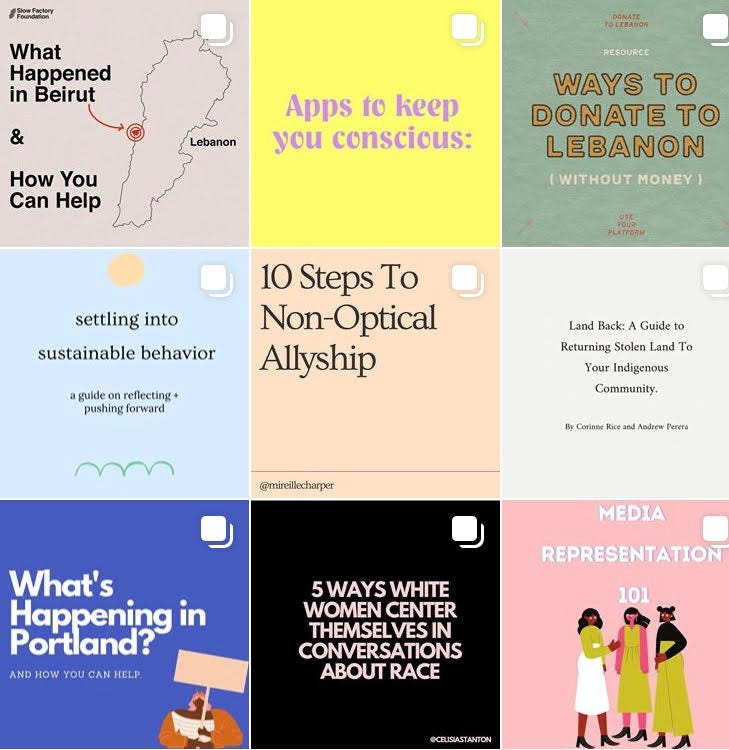

Since the onset of the pandemic in America this spring, Instagram has been saturated with thousands of glossy, informative slideshows that conveniently break down our most important political issues into beautiful, bite sized chunks. A 10-page slide show on the crisis in Beirut; a guide to returning land to indigenous communities; a step by step model for non-optical allyship, and the list goes on and on. The information is usually curated by activists, academics, or regular folks with the time and knowledge, and is rapidly shared through Instagram stories. When I first encountered these infographics a couple months ago, I was immediately impressed by the range of people engaging with them: suddenly apolitical family members and white people I knew in high school cared about race, politics, and foreign affairs in a way I had never seen. It made me wonder, have folks on Instagram found a way to package the news that is more accessible, or do people care more about the news because of its aesthetic?

Merriam Webster defines “aesthetic” as something that is “pleasing in appearance,” which certainly describes many of the infographics circulating on Instagram today. As opposed to a traditional print or online article which normally utilizes black text on a white background with maybe one or two photos or video clips, these Instagram slideshows employ bright colors, bold fonts, stunning imagery, and other visual tactics to draw the reader in. While Instagram’s innovation has certainly tuned more people into the news, the history of people engaging in journalism because of it’s aesthetic far precedes our current moment. Along with the shift from print to online media came the need for a new head in the newsroom: an audience engagement expert. According to 2015 reporting from the Columbia Journalism Review, audience engagement editors are “the children of the copy editor, the public editor, and the paperboy” who “wield heavy influence in the industry, shaping both how journalists cover events and how readers consume news.” These editors are not responsible for editorial content, but how the content is laid out online, making crucial decisions about font, color, art, headlines, and other factors that can help increase web traffic and, by extension, advertising dollars.

“Uncountable factors including headline text, article text, language, subject matter, and imagery can impact whether a certain piece of content is likely to see wide distribution online,” Angie Jaime, a journalist, audience editor and strategist, and community builder based in Brooklyn, told me in an email. “It's a confluence of these things that creates something akin to ‘virality.’ This is a word I detest but it’s handy to describe a certain level of volume of engagement.”

While factors such as font or headlines can determine how many people engage with content, there is also proof that certain types of media get far more engagement across the board. According to a 2018 study conducted by the Pew Research Center, 47% of Americans prefer to watch their news through TV while only 34% prefer to read it, and several studies confirm that less Americans read for pleasure today than at any point in the country’s history. This perhaps explains why, throughout the 2010s, many news outlets made the decision to “pivot to video,” or make more visual content rather than produce editorial work. It seems in 2020, journalists have decided to “pivot to Instagram,” creating informative and beautiful graphics that spread like wildfire, becoming the writer and the audience engagement editor in one.

Haaniyah Angus, a 21-year-old Black film student and culture critic based in England, made the decision to create infographics on Instagram rather than publish her articles through more traditional avenues in July, giving two main reasons: firstly, the recession caused freelance budgets to dry up so that Angus was having trouble finding work, and secondly, she found that writing for Instagram often gave her a bigger audience. “People are more likely to read shorter form articles,” Angus explained. “When I look at my graphics on Medium, the views versus reads never match up. I still do publish long form articles because I love to write, but I’ve realized that we do live in a generation where people have shorter attention spans, so it helps if you’re able to take these pivotal moments and turn them into something shorter and simplified.”

On her Instagram, Angus has written several short form articles in the form of artistic slideshows on topics like cancel culture, Black womanhood, and the male gaze. Her posts are in line with the typical aesthetic of an Instagram infographic: fun fonts, bright colors, and engaging images along with short and snappy text. However, the format of the graphic does not take away from it’s journalistic merit: each post is thoroughly researched, well sourced, and written in clean, accessible language. The only difference between Angus’ post on the male gaze and a traditional op-ed is that Angus’ graphic is easier on the eyes.

Aside from their brevity, another potential reason behind the popularity of the newfound Instagram Article is it’s accessibility. Not only are Instagram slideshows easy to share via your story, they are also available to anyone who has the app. This comes in stark contrast to mainstream outlets such as The New York Times, The Atlantic, or The Washington Post, where readers are only allowed a handful of free articles per month. Because these infographics are being posted on Instagram, a platform with a relatively young user base, they also allow for a discussion of politics in a more informal or conversational way.

The Instagram Article not only creates increased access for the reader, but for the writer as well. While some journalists like Angus have taken their craft to social media, many people publishing infographics on the platform are not professional writers, but rather activists, academics, or people on the ground. Hayley Craig, a 19-year-old college student from Maryland, told me she made an infographic about police brutality in Portland after being disappointed by the traditional media’s coverage of the event, and said that the post was shared far more than any other photo she had put on the platform.

“I wanted to make an infographic on Portland because what I was reading and watching from my independent news sources didn't match up with a lot of what was being shared on Instagram,” she said. “There was a lot of emphasis on Trump and the feds being the source of escalation, but not enough on the equally hideous actions and compliance of Governor Wheeler and the Portland police.”

“The response was really positive,” she continued. “I saw a number of people reposting [the graphic] on their stories and tagging me. They said it was really informative and they appreciated that I cited sources. Also I noticed I got a few more followers after I posted the infographic and other flyers.”

Craig’s experience hits at the heart of how the Instagram Article has changed the game: now, a diverse group of people, and not just professional journalists, can be successful in curating or circulating the news. In a way, Instagram has brought journalism back to it’s proletarian roots. While many view journalism as an elite field today with schools like Columbia and Northwestern offering competitive graduate programs and contemporary reporters like The New Yorker’s Jia Tolentino garnering book deals with nation-wide tours, this was not always the case; in fact, a 2016 Atlantic article reports that in 1960, only about one third of journalists had never attended a year of college, with the number dropping to 8.3% by 2015. This newfound elitism in the field has alienated audiences, explaining why consumers are turning elsewhere. The success of the informational Instagram graphic confirms that while experience in a newsroom may teach you technical editorial skills, it can’t teach you how to stay in touch with the needs of the general public, an area where the field maintains gaping holes.

Elitism in journalism has manifested in a number of ways: namely, in a newfound desire for college-educated reporters with class privilege and an insistence that this perspective is one to be heralded as “objective” and true. Journalists have traditionally been taught to remain objective in their reporting––ie, show both sides of a situation in every story to avoid any bias in their language and framing. However, recent years have fostered frequent debate about the definition and purpose of objectivity in journalism, particularly when serving marginalized communities. While objectivity might sound like a moral aspiration to some, it’s often quite difficult to achieve: even the notion of what’s considered objective is, in itself, subjective, and since only 17 percent of newsroom staff in the United States are not white as of 2018, an “objective” viewpoint is too often one entrenched in whiteness. Not only is journalistic objectivity a limited scope, it’s also ineffective when discussing many topics. In order to remain objective when reporting about the Black Lives Matter movement, for example, a reporter might use a police officer as a source in order to “show the other side” of the protest, a tactic which could both downplay the reality of racist police violence and alienate audiences who are reluctant to trust cops as reliable sources. What’s more, while traditional media may insist on showing multiple perspectives in every story, they are almost never given equal weight––recent data from FAIR Media Watch reports that of the 172 op-eds published in The New York Times and The Washington Post since the onset of the protests in May, only 2, or about 1%, were written by actual protestors, while the rest were written by journalists, politicians, and other non-activists. The right-leaning scope of traditional media practically necessitates social media journalism, a space where activists and leftist voices can be given a platform to share their ideas.

The popularity of Instagram journalism also illustrates how a growing number of Americans are growing to dislike or distrust traditional news. While the idea of “fake news,” or false and often sensationalized news stories told for a specific political agenda, was popularized by Donald Trump and his conservative cronies ahead of the 2016 election, leftists have lately had to battle their own slew of bad takes, centrist clickbait, and overall fake information from the so-called “free” press. Amid publications siding with the police, downplaying or ignoring racism, and refusing to hold politicians accountable for harmful actions, the Instagram Article becomes a refreshing break from journalism that is seemingly committed to upholding the status quo. Craig’s sentiment that she felt compelled to write an article about Portland after seeing mainstream news downplay police brutality at the protests illustrates this point perfectly––if more of America is leaning left and the press refuses to budge, this means people must make and circulate news outside of the traditional press. The diversity of voices contributing to journalism on social media is also a testament to this: both Craig and Angus, as young Black women and students, represent demographics that are seldom heard in mainstream media, but on Instagram, their voices are amplified.

“The more content shared on Instagram that is aesthetically pleasing, packaged well, and leverages highly stylized information, it creates the democratization of professional aesthetics, or an upending of the politics of aesthetics,” Jaime, the engagement editor, explained. “Who gets to create and disseminate information that is ‘professional’ and therefore believed and accepted? It's more influx now.”

As much good as the Instagram Article has done, it also raises some complicated questions. If Instagram infographics are considered journalism, should they be held to the same standard as articles published through mainstream publications? Can these slideshows be trusted if they haven’t been edited or fact checked by someone with journalistic experience, as most traditional articles are? Caroline*, a fact checker and research editor based in New York City, would caution us to tread lightly. “What gives me pause about these Instagram posts is that they’re very prescriptive,” she explained. “It’s often, ‘here are 10 steps to do this thing’, and it’s all written in a very definitive tone. Meanwhile, so much of the conversation about allyship, for example, is not definitive. So the question of ‘what is performative allyship’ is tricky, because if you ask ten different people, you’ll get ten different responses. But people often present these issues as if they’re straight facts and not one person’s perspective.”

“As part of my job, I try not to read too much into these accounts but it’s hard,” she added. “I often wonder, who’s behind this account? How many people are there? Did they run a poll to get this information? Sometimes it’s hard to tell.”

Caroline continued that a good portion of a researcher or fact checker’s job hinges on creating a distinction between “fact” and “truth” in every story. While there is no hard and fast rule to this characterization, it seems that, like the notion of objectivity, the fact versus truth dilemma also causes controversy. For example, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, several widely read mainstream news outlets including CNN, The Washington Post, and The Associated Press referred to Derek Chauvin, the white police officer who murdered George Floyd, as a cop who “knelt on a man’s neck,” ensuing outrage from many readers. People were not upset by this characterization of Chauvin because it was not factual, but because in their quest for the facts, these journalists had completely obscured the overarching truth of racism and police brutality towards Black Americans. There seems to be a growing desire for truth over fact from readers across the board, which perhaps explains why Tom Cotton’s New York Times op-ed advocating for military presence at protests caused the largest number of subscription cancellations in twenty-four hours in The New York Times’ history. On Instagram it seems, the creators of news are writers, audience engagement experts, and research editors as well, drawing the line between fact and truth in a way that many mainstream news orgs seem incapable of.

“Being a journalist is not like being a doctor in that you don’t need to go to school to be able to do your job,” Caroline said. “Anyone can write or post something that’s informative, and I recognize there are a lot of people, young people especially, doing tremendous work on social media right now. I think people should engage with those posts if they want to, but they should read the news as well.”

Caroline’s point brings us full circle: should we be concerned that people are not interested in reading the news, more excited by glossy Instagram slideshows than a full length, traditional article? In her recent essay for Vox, writer Terry Nguyen offers up a different explanation for the recent popularity of Instagram activism: amid the pandemic, she writes, “it no longer felt appropriate, even for celebrities and influencers, who tend to exist unfazed by current events, to skip over politics and resume regular programming,” and so “the unexpected solution to this posting ambivalence came in the form of bite-sized squares of information.” Nguyen brings up a good point: it’s perhaps naive to trust that Instagram, a platform widely known for a racist, sexist, and fatphobic algorithm, would be the site of any sort of political revolution, and many of the people reposting graphics are most likely doing so to make their feed look nice, or keep up with a trend. However, while posting or even creating an infographic is not in and of itself a sufficient form of activism, it’s impossible to ignore how many of these slideshows have significantly increased the likelihood of people engaging in politics or the news.

More than anything, the Instagram Article has given people a way to take the news into their own hands. Across America, quarantine has brought about a wave of anti-establishment resistance unencountered in the country’s recent history. Many have spent their months at home making their own clothes, baking their own bread, refusing to buy from large corporations, and making other moves that, big or small, divest their time, money, and energy away from the racist and capitalist systems that have historically governed us. The Instagram Article has contributed to this trend: in creating our own news, we are disassociating from a press that has whitewashed, erased, and largely failed the most vulnerable populations in this country, and boldly insisting that we have control over our own narratives.

Thank you so much for reading! If this story spoke to you, please consider sharing with a friend or two. If you have the means and would like to support me, feel free to do so through Venmo (@Mary-Retta) or Paypal (maryretta33@gmail.com). If you’d like to see more of my work, you should subscribe to this newsletter or follow me on Twitter (@mary__retta.) Be well and more soon!

xoxo

mary <3

*This source preferred not to use her real name.