Click here to read this essay on Substack.

I know I’ve started every essay like this lately, but the other day on Twitter I scrolled past an image that stopped me in my tracks. On October 4th, Twitter user @k0rdon, a 19-year-old artist based in Ireland, posted a meme he created depicting Donald Trump as a queer college student. According to the fictional universe @k0rdon has created, Trump is 19 years old, uses he/they pronouns, and is studying as a Business major. He is also successful on Etsy, an asthmatic anime fiend, and, insanely, dating Joe Biden. In @k0rdon’s image, Trump stands shyly, grasping an inhaler between painted fingernails, sporting a red “MAGA” mask and a tattoo on his arm that reads, “met god, he’s a proud boy.”

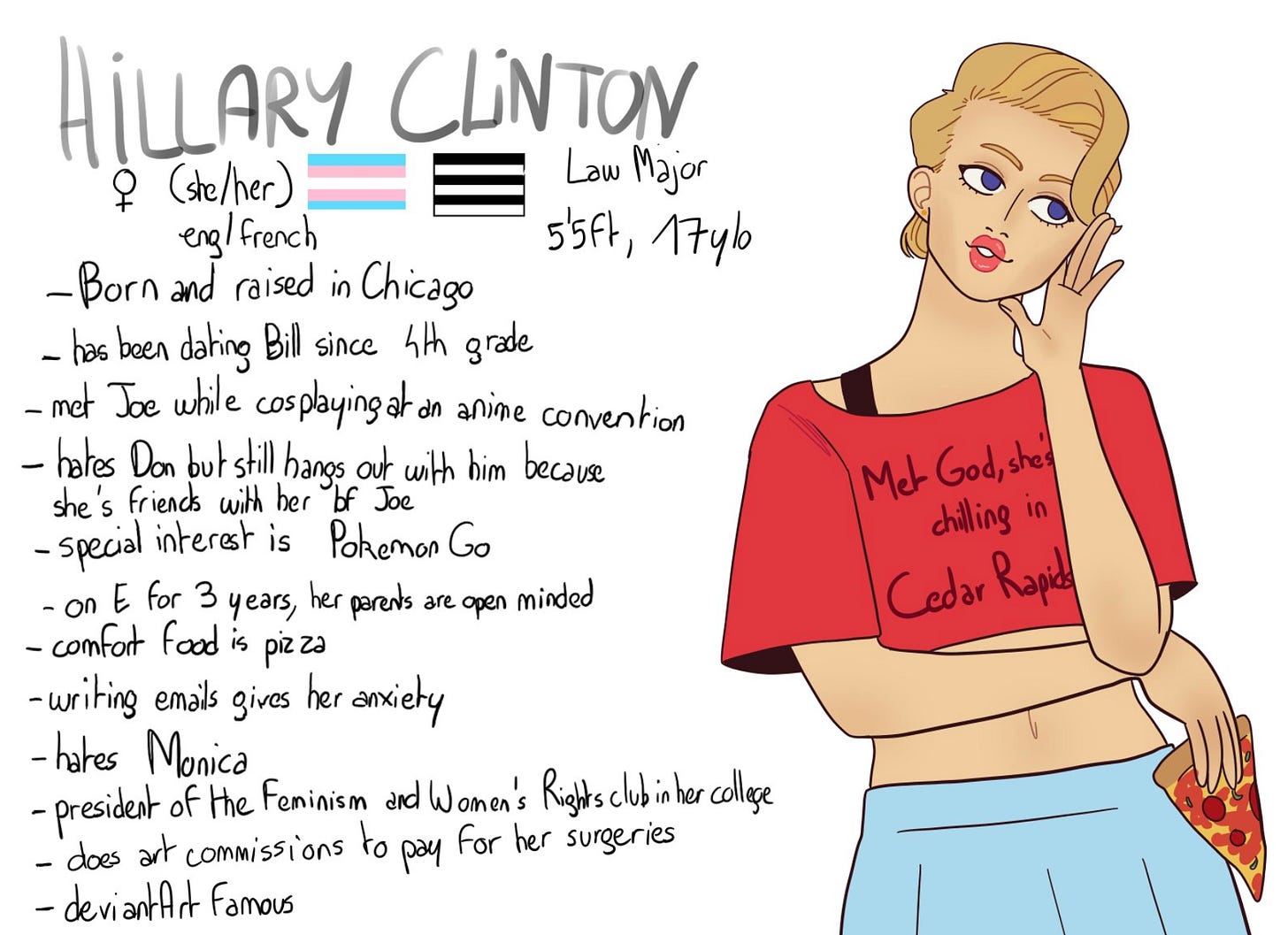

Needless to say, @k0rdon’s meme received extremely mixed feedback. The tweet garnered over 25,000 likes, with many comments marveling over the alternate universe the artist had created. But others users were understandably upset by the memes, calling them strange, unnecessary, or just overall inappropriate. These criticisms did not slow @k0rdon down, however: in the following days, he created several other memes that similarly depicted both Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton as queer college students. In Biden’s image, the candidate sports a lavender sweatshirt proclaiming “if God doesn’t vote for me, then she ain’t Black;” in Clinton’s image, she is portrayed as a 17-year-old transgender law major who has anxiety and “hates Monica.”

Seeing these images on my timeline was a confusing experience, one of those things where I didn’t know if I should laugh or cry. On the one hand, these memes are so fucking outrageous––it’s unfathomable to me that someone could look at our current political situation and think, you know who might have some keen insight into the rise of fascism in America? Fictional gay college kids. I’ll admit that some aspects of the memes made me chuckle: in Biden’s, the candidate is wearing a “MAGA” shirt underneath his sweatshirt, next to a caption that reads “wears Don’s handmade MAGA merch even though he disagrees with it,” which is a pretty good summation of the centrist liberal “civility” politics we’ve seen going on in the election as of late. But what concerned me about these memes is that on the whole, they weren’t made out of irony––they were made earnestly. @K0rdon bases many of his memes in some variation of the truth––Donald Trump was a business major from New York, for example, and Joe Biden is in fact from Pennsylvania and Delaware, as the image proclaims––but the specific ways the artist chose to fictionalize these politicians disturbed me. In reimagining Trump, Biden, and Clinton as young queer and trans people, @Kordon is likening these politicians to one of the most targeted demographics under either political party, as well as one of the biggest opponents of electoral politics generally. @Kordon’s depiction of these politicians is clearly meant to make them seem cute, quirky, or relatable––they’re gay! They’re students! They have anxiety, just like me!––which is not only a false narrative, but a dangerous one. But the popularity of these images also begs the question: why are people so inclined to meme fascism?

Political memes have been on the rise for years now. In March of last year, writer Sage Lazzaro penned an essay for VICE on this very topic, noting, “simple to make and simpler to distribute, [memes] can communicate a stance or message at a glance and express the same feelings experts say are behind conventional protest art.” As Lazzaro points out, there are several reasons behind the virality of political memes: not only are they easy to share on social media, but as an image-based medium, they are more easily digestible to the average person than political theory, and can make politics more accessible. Lazzaro writes that political memes have flourished in America under Trump’s presidency and I would agree: accounts like @atmfiend have provided excellent political commentary over the last few years on issues such as sex work, drug use, and sexual assault using clever means to communicate more complicated messages. Last week, Chicago-based rapper Noname also shared a political meme which featured two people, presumably in the Middle East, standing precariously close to bombs being dropped by planes sporting an American flag. “They say the next ones will be sent by Biden,” one person says to which their friend replies, “really makes you feel like you chose the lesser evil.” Some of Noname’s followers were upset by this, with one replying to her tweet that the meme was “ignorant.” In response Noname wrote, “the meme is a reminder that under american democracy people will always die. it’s not ignorant, it’s historically accurate.” Noname’s analysis pinpoints the crucial difference between a failed and an effective political meme. Both use images and catchy text to break down complex political situations into accessible, if slightly absurd scenarios. But in a successful political meme, it should be the system, or those who support and uphold it, who remain the butt of the joke. In Noname’s meme, Biden, who upholds the long-standing American traditions of racially motivated genocide and war crimes, is rightfully reduced to an ineffective liberal pawn; in @Kordon’s meme, he is absurdly celebrated as a bashful, democratic queer teen.

Because memes have become a popular form of discourse, politicians can also use them to control a social or political narrative. During the Vice Presidential Debate earlier this month, memes were abundant on both sides: Mike Pence, for example, graced many a Twitter feed as an image of him with a black fly stuck in his hair quickly went viral, causing the internet to muse over whether the fly represents an omen, a distraction, or, disappointingly, Black people themselves. As for the Democrats, Kamala Harris’ exaggerated facial expressions too were quickly memed after the debate, garnering mixed responses from folks online. On Twitter, some claimed that Harris made these intense facial expressions on purpose, as she and her PR team knew that users would be quick to make memes that kept the politician in the forefront of our internet discourse. Others, however, were sympathetic towards the candidate, arguing that as a Black woman, she made these facial expressions because if she were instead to speak out and interrupt Pence––which she did at one point, insisting, “I’m speaking,” before insisting she was pro-fracking––she would be vilified, or labeled an “angry Black woman.”

The latter response indicates how politicians in America can successfully wield the “political meme”––and a larger failed project of identity politics––to their advantage. Harris’ team would like the American public to believe that as a Black woman, she automatically has less voice, less influence, or less power than Mike Pence, or other white men who might challenge her to a public debate. This may, on the one hand, be true––I don’t doubt that had Kamala Harris clapped back at Pence on screen, the right-wing “angry Black woman” response from conservatives would have come immediately. (This is particularly relevant as meme reactions are often rooted in Black expression, and many non-Black people use memes or images of Black folks when reacting to something online.) But Harris is not powerless, and to pretend so is not only historically inaccurate, but a purposeful misrepresentation of identity politics on behalf of the Democratic party to mask the candidate’s history of xenophobic, racist, and carceral policies. In signing up as Biden’s VP, Harris willingly engaged in this debate––it’s preposterous for her to enthusiastically sign up to participate in a US election, a system rooted in racism and misogyny in practically every conceivable way, and then claim she cannot engage fully because of her gender or race. Ultimately, the only identity that matters here is not Harris’ race or gender, but her political party as an American capitalist––and here, that puts Harris, Pence, and the rest of the members of the American government on exactly equal footing. And this is where the Harris memes so blatantly miss the mark: in focusing on Harris’ exasperation at Pence for his political views or tendency to interrupt a woman, the images draw a false dichotomy between the Democratic and Republican parties, suggesting that Republicans are rude or misogynistic while Democrats are patient and kind. Rather, a successful political meme would be able to acknowledge that in both candidates agreeing to participate in this debate, both parties have foolishly put their faith in a useless political debate as a valuable use of time, money, and energy, indicating that the two political parties are more similar than they are disparate.

Which brings us back to why @Kordon’s images, though amusing, fail to deliver in the way political memes should. A good political meme can, if only for a moment, take the power straight out of the hands of a fascist dictator and deliver it to the people, by allowing us to reduce a terrifying, racist, serial murderer like Trump into something small, stupid, and unintimidating. A political meme can only succeed if politicians themselves remain the butt of the joke.

Thank you so much for reading! If this story spoke to you, please consider sharing with a friend or two. If you have the means and would like to support me, feel free to do so through Venmo (@Mary-Retta) or Paypal (maryretta33@gmail.com). If you’d like to see more of my work, you should subscribe to this newsletter or follow me on Twitter (@mary__retta.) Be well and more soon!

xoxo

mary <3